Digitalization X Sustainability

Reading time approx.15 min.

Digitalization within supply chains and value added chains provides new opportunities to reduce resource use, thereby mitigating climate change. But we will be unable to do so unless we properly understand and design digital technologies to facilitate this process. Digital forecasting systems and intelligent integration are rapidly establishing themselves in almost all market segments. Navigation systems predict optimal routes, leading to fewer traffic jams, and reducing the amount of fuel burned. Smart Homes know in advance when their inhabitants use the most electricity, and ensure that batteries in the garage – charged via solar panels on the roof – are full when required. Decentralized units for delivering renewable energies are ready for mass production, and increasingly capable of autonomous management and coordination.

In the food industry, too, digital change is leading to more sustainability. Every evening at 10 p.m., several million data sets make their way from the German supermarket chain Kaufland to a company called BlueYonder, with headquarters in the German city of Karlsruhe. The data sets contain daily sales data from every cash register at all 1,350 locations. Kaufland’s turnover averages around €73 million per day. The supermarket sells around 80,000 different items. The data Kaufland sends provides more information than just how much profit was made that day, what items are in stock, and what the chain’s liquidity looks like. Instead, the data sent to Karlsruhe are fed into a kind of digital crystal ball.

What at first glance seems to be a gigantic monitoring machine may turn out to be the solution to the climate crisis. It could contribute significantly to a reduction in the amount of resources used by industry, commerce, logistics, and during transport. Fewer goods delivered to the wrong location, fewer kilometers driven, fewer surpluses, and perhaps most importantly of all, less food rotting on the shelves only to be thrown away. BlueYonder, located in Karlsruhe in southern Germany, wants to make that possible. The company, which was founded ten years ago as a spin-off of the local University of Applied Sciences, has gone through several rounds of take-overs by software firms in the USA and is now one of the world’s leading companies in the realm of retail forecasting software. Additional data is added to the daily sales data:

And all that data comes together to allow BlueYonder to make a forecast. The forecast predicts which products will, in all likelihood, be sold in which amounts tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, and during the next week. An example of these predictions might be how many cartons of a certain brand of milk will be scanned at checkout in a Berlin branch of the store over the next few days. Or pick another product: apples, sausages, household goods, practically every item offered by the store, a total of around 80,000 different goods. The forecasts calculated by BlueYonder are 73 percent accurate; the software engineers are only wrong 27 percent of the time. But that is going to change soon. Currently, the analysts can look about a week into the future and return results much better than those they would get based on chance. After a week, however, the precision of their forecast drops dramatically. But a week’s notice is more than enough to manage logistics and the flow of goods.

It turns out that this staid old supermarket chain is one of the most innovative retailers in the world. And of course if they can do it, if they can use modern technologies and associated methods, such as machine learning and artificial intelligence, then it’s safe to say that those technologies aren’t going anywhere. This is not a beta-test for the future: these forecasting systems are working and productive, right now, able to autonomously direct company logistics.Even the upstream disciplines and industries essential to the grocery business are involved: commerce, logistics, and the food industry are currently in the process of integrating digitally with one another.

The goal: if we are able to embed accurate predictions directly into industry and logistics processes, companies will be able to produce and deliver items more in line with demand.

The promise: less food that has to be thrown away, fewer goods arriving at the wrong locations, less required warehouse space, fewer vehicles needed, less refrigeration, less repackaging, packaging for transport, new packaging, fewer resources used, less CO2.

And it’s not just the food industry:

Digital technologies appear to the be the key to global sustainability.Many different studies have shown that sustainability can only be achieved after the biggest greenhouse gas emitters have achieved digital integration and digitalization.With a total of 93%, the largest greenhouse gas emitters are:

The agricultural industry

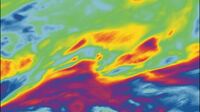

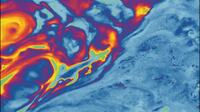

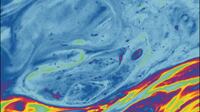

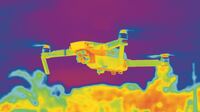

Digitally controlled and networked devices are already making inroads into the agricultural industry:they are making available individual location data, data from sensors in the soil, weather and weather predictions, pictures taken by drones and in particular by satellites that can, every 24 hours, so practically in real time, monitor and analyze fields and agricultural land. And all this data can be used to practice an entirely new type of agriculture, making use of knowledge that, until now, was simply inaccessible.

The digital, automated interpretation of image data, for example as a means of determining information regarding the growth rate of plants, is these days considered a standard product. Even for those images taken from orbit. This allows us to compare areas with similar soil and climate conditions and discover, for example, what it is that farmers who achieve better yields using less energy and fewer pesticides are doing better than farmers who are not getting the same results. Suddenly there is a global benchmark available for comparison.

And these developments are necessarily changing how agriculture works. Farmland and fields are no longer considered uniform entities, with every square meter to be treated identically. Individual fields can be broken down into smaller and smaller sections. Now, agricultural equipment knows which locations are always a little too damp or too dry, where the good quality soil is and where the quality is not quite as good, which positions require a little more or maybe a little less fertilizer. The equipment knows and makes autonomous decisions about the precise amount of fertilizer that each individual square meter needs. And the same is true for crop protection. Damp locations prone to fungal infestations can be targeted explicitly instead of spraying the entire field.

Autonomous robots, trained using machine learning, are able to independently search for pests and kill them mechanically or using lasers. The ancient labor-intensive practice of scouring the field for insects and killing them by hand, as practiced by our grandparents, is suddenly no longer labor intensive and thus profitable once more. French and Australian manufacturers are already offering whole fleets of small robots, about the size of a riding lawn mower, designed for use in vegetable farming. Over the next few years, we will see a switch from treating entire fields to treating individual plants, from herd management to managing individual animals. But the farmers themselves, who will, no doubt, in order to be certain, continue to spend a lot of time in the fields, no longer knows what it is exactly that their equipment is doing. It is autonomous, deciding on its own what is to be done and where. Begging the question as to whether farmers will become this decade’s equivalent to Uber drivers.

But regardless of how we view the increasing trend towards the use of digital platforms both on the market and in society, we must acknowledge that the correct implementation of modern technology – even taking into account all associated risks – can be part of the solution for creating a sustainable, ecological, more climate friendly, and therefore future-proof agricultural industry.

Media, social media and search engines

But the forecasting systems mentioned at the beginning of this piece are finding a broader range of application than mere logistics and industry. Media, search engines, and practically every social media platform in existence also make use of systems to predict consumer behavior. At first glance this may seem harmless; a recommendation algorithm that is well tuned to match the user’s preferences may even be seen as a benefit.But is it?

If Facebook, for example, uses my internet history and click behavior to conclude that there is an 80 percent chance that I will begin dieting or buy a car within the next six weeks, then the platform – not to mention other platforms that track my internet use via cookies – will start showing me more and more advertisements and information on potential diets or new vehicles. In turn, my chance of starting a diet, or buying a car, increases with the number of ads I see promoting such things. The artificial intelligence initially designed to respond to my needs is now manipulating my behavior.

Douglas Rushkoff, an author from the USA, asks: what happens to the remaining 20 percent chance? Is this technology grinding away at certain types of divergent, surprising, or unexpected behavior? Is it possible that within two weeks, 80 percent has turned into 85 percent and a mere two weeks after that the probability will be sitting at 95 percent?

Authors such as George Orwell and Aldous Huxley created dystopian futures in which people were at least able to recognize that they were being manipulated. This new type of manipulation is so subtle that we don’t even notice it – or if we do, we do so mainly by noticing the symptoms, such as the erosion of social solidarity. We are currently in the middle of a transformation process that affects almost all areas of our lives. Rapid technological advances have turned processes into fundamental applications that many, until now, have considered science fiction. Artificial intelligence, for example, is the fundamental technology of this decade. And as with any technology, it opens the door to as many opportunities as it does to problems.

New technologies are not magic potions

These new technologies are not magic potions that can be poured onto everything and anything, transforming it into a force for good, although much good is being done:Food waste is decreasing Conventional agriculture – largely obsolescent from today’s perspective – is becoming sustainable. There are fewer climate problems, we can feed the world, the divide between the global north and global south is closing. Neither are they fundamentally damnable, provided we don’t wish to pack it all in and return to a pre-industrialized world.

This dualism is the inevitable consequence of every technological transformation: just as industrialization lifted many out of poverty, improved hygiene, and cured many an illness, it also caused diseases of affluence to spread like wildfire, and either cemented or worsened injustice and exploitation in many areas of the world. In the end, it has caused a situation in which our planet is in the middle of a crisis from which we may not emerge intact.If we consider the initial push for digitalization at the beginning of the aughts to be an earlier technological advance, then we must acknowledge that in that case, the new technologies ushered in an era of platform capitalism, continued the devaluation of unskilled labor, created a small number of dominant tech-monopolies, contributed to the shrinking number of mid-sized businesses, emptied city centers – all without any significant improvements to the environment, the rate of climate change, or social issues.

These problems are not caused by a lack of democracy, inadequate social justice, legal conditions, the ability or inability to participate in society, abuses of power, corruption, ruthless exploitation of resources, and so on – they are caused by our failure in the past to engage with and shape technological transition periods.

But this time, there is more at stake. In addition to old problems becoming increasingly more urgent, we have a whole set of new problems: surveillance, social credit scoring, algorithms that discriminate, marginalization, and polarization within society.

And now more than ever, technological advances are met by a civil society and political reality that barely understands them and does not fathom how comprehensive their use already is or the scope of their implementation, to say nothing of how all-encompassing they will be in the future. Unfortunately, current debates regarding these new technologies are unsophisticated, in some cases naive, often populist and even, dare I say it, incompetent.

If everything is done digitally, then the digital world no longer runs parallel to our world, like a TV that you can turn off whenever you want to. It can no longer be considered “virgin ground”, as Angela Merkel called it in 2013, or the realm of science fiction. No, at that point the digital world will be anchored at the core of our civilization. There will no longer be a divide between digital and analogue spaces. The divide is vanishing as we speak. The digital world has long been just as much part of our public space as public squares and streets.And just as we regulate public spaces, we must begin regulating digital spaces.

But to do this, to constructively include these issues in political decision making processes, to be able to competently discuss them in civil society and in politics, and finally to be able to make prudent political decisions, we need to become experts on the subject.The goal is to understand and shape this new core facet of our world. And it’s time we got started.

Discover more:

The new language of packages

Since when can packages talk with each other? And in what language? Since when can supply chains think? And can they also think ahead? With IoT, virtual reality and live reality are merging to form the New Reality. And what do we get out of it?

The eternal circle

What if profitability and sustainability are not a contradiction in terms? But a product? What if circular economy isn't just an idea? Is it a necessity? How circular economy can find ways to save the planet - when we are ready for it.

Olaf Deininger – Author

The business journalist and digital expert looks back on many years of experience in leading positions, including Editor-in-Chief of the "handwerk magazin" (2014 to 2020) in Munich.

Even the upstream disciplines and industries essential to the grocery business are involved: commerce, logistics, and the food industry are currently in the process of integrating digitally with one another.

Even the upstream disciplines and industries essential to the grocery business are involved: commerce, logistics, and the food industry are currently in the process of integrating digitally with one another.

The goal: if we are able to embed accurate predictions directly into industry and logistics processes, companies will be able to produce and deliver items more in line with demand.

The goal: if we are able to embed accurate predictions directly into industry and logistics processes, companies will be able to produce and deliver items more in line with demand.

The promise: less food that has to be thrown away, fewer goods arriving at the wrong locations, less required warehouse space, fewer vehicles needed, less refrigeration, less repackaging, packaging for transport, new packaging, fewer resources used, less CO2.

The promise: less food that has to be thrown away, fewer goods arriving at the wrong locations, less required warehouse space, fewer vehicles needed, less refrigeration, less repackaging, packaging for transport, new packaging, fewer resources used, less CO2.

Many different studies have shown that sustainability can only be achieved after the biggest greenhouse gas emitters have achieved digital integration and digitalization.

Many different studies have shown that sustainability can only be achieved after the biggest greenhouse gas emitters have achieved digital integration and digitalization.

Digitally controlled and networked devices are already making inroads into the agricultural industry:

Digitally controlled and networked devices are already making inroads into the agricultural industry:

But is it?

But is it?

what happens to the remaining 20 percent chance? Is this technology grinding away at certain types of divergent, surprising, or unexpected behavior? Is it possible that within two weeks, 80 percent has turned into 85 percent and a mere two weeks after that the probability will be sitting at 95 percent?

what happens to the remaining 20 percent chance? Is this technology grinding away at certain types of divergent, surprising, or unexpected behavior? Is it possible that within two weeks, 80 percent has turned into 85 percent and a mere two weeks after that the probability will be sitting at 95 percent?

We are currently in the middle of a transformation process that affects almost all areas of our lives.

We are currently in the middle of a transformation process that affects almost all areas of our lives.

These new technologies are not magic potions that can be poured onto everything and anything, transforming it into a force for good, although much good is being done:

These new technologies are not magic potions that can be poured onto everything and anything, transforming it into a force for good, although much good is being done:

These problems are not caused by a lack of democracy, inadequate social justice, legal conditions, the ability or inability to participate in society, abuses of power, corruption, ruthless exploitation of resources, and so on – they are caused by our failure in the past to engage with and shape technological transition periods.

These problems are not caused by a lack of democracy, inadequate social justice, legal conditions, the ability or inability to participate in society, abuses of power, corruption, ruthless exploitation of resources, and so on – they are caused by our failure in the past to engage with and shape technological transition periods.

But this time, there is more at stake. In addition to old problems becoming increasingly more urgent, we have a whole set of new problems: surveillance, social credit scoring, algorithms that discriminate, marginalization, and polarization within society.

But this time, there is more at stake. In addition to old problems becoming increasingly more urgent, we have a whole set of new problems: surveillance, social credit scoring, algorithms that discriminate, marginalization, and polarization within society.

And just as we regulate public spaces, we must begin regulating digital spaces.

And just as we regulate public spaces, we must begin regulating digital spaces.

The goal is to understand and shape this new core facet of our world. And it’s time we got started.

The goal is to understand and shape this new core facet of our world. And it’s time we got started.